PREVIEW

- What social and cultural rights might be included in the National Education Law?

- What are the four Race and Religion Protection Laws? What do you know about them?

- What rights do you think persons with disabilities have in the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Law?

- How do you think the Ethnic Rights Protection Law defines “ethnic group”?

National Education Law, 2014 (Amended 2015)

The purpose of this law is to improve the education provided in Myanmar. This includes access to, quality of and inclusion within education. The law recognises and covers many different types of education, which are defined in Chapter 1 and described within the national education system in Chapter 5. The law establishes a National Education Commission that is responsible for overseeing the objectives and principles stated in the law. The National Education Law is to be supported by by-laws related to basic education, higher education, private school education, and technical and vocational education and training.

Some of the human rights relevant for minority groups in this law include:

- This law defines national education as “education that values, preserves and develops the language, literature, culture, art, traditions, and historical heritage of all the ethnic groups in the nation” and it is therefore inclusive of ethnic minority groups. Related to this, the law states that teachers should value “the language, literature, culture, arts, traditions and historical heritage of all ethnic groups”.

- The law states that the Ministry of Education along with Regional and State Governments should “help to open classes to develop the ethnic groups’ literature, language, culture, arts and traditions and to start subjects/majors in ethnic groups’ culture, literature and history in universities”.

- Burmese and English are recognised as the two primary languages for instruction. However, article 43 allows for ethnic minority languages to be used alongside Burmese language at the basic education level, as in multilingual education.

- Article 44 allows for Regional and State Governments to begin implementing ethnic minority language and literature classes, starting at the primary level.

- Article 36 states that schools will be established with special education programmes for persons with disabilities and allows non-governmental organisations to open private schools for persons with disabilities.

- Article 41(b) states that “curriculum standards” will be established for persons with disabilities in special education programmes.

There are some restrictions and violations of minority rights in this law:

- This law refers to taingyintha and thereby excludes ethnic minority groups that are not classified as taingyintha.

- The law does not address any education services for persons lacking legal citizenship status.

- This law does not recognise non-state education systems managed by ethnic minority groups, nor does it recognise the right for ethnic and indigenous groups to have their own education systems. Education about “ethnic group’s literature, language, culture, arts and traditions” is therefore regulated by the government.

- This law focuses on establishing special education programmes for persons with disabilities and does not explicitly encourage their mainstreaming into regular school programmes.

- The definitions of “non-formal education” and “community-based education” in Chapter 1 are vague. This may affect education services delivered by and for minority groups, which are often described as “non-formal” and/or “community-based”.

Race and Religion Protection Laws, 2014-2015

The Myanmar Buddhist Women’s Special Marriage Bill was adopted in 2014. This law regulates marriages between Buddhist women from Myanmar and non-Buddhist men.

Some of the human rights relevant for minority groups in this law include:

- The law helps to ensure that marriages are officially registered.

- The law could provide protection against forced religious conversions.

There are some restrictions and violations of minority rights in this law:

- This law assumes that interfaith marriages between Buddhist women from Myanmar and non-Buddhist men have a higher risk of being coercive or non-consensual. This is a discriminatory assumption that targets non-Buddhist men, who are also at risk of facing punishments under this law, including fines and imprisonment.

- Buddhist women from Myanmar and non-Buddhist men who live together, whether they are a couple or friends, are presumed to be married under this law and required to register as a married couple. This rule restricts the right of people of different faiths to live together without marrying each other.

- Interfaith marriages between Buddhist women from Myanmar and non-Buddhist men are required to be announced to the public and are open for objections for 14 days. If any objection is received, a court will investigate whether the criteria for marriage is fulfilled or not. The court decision is final (article 18(d)), which means that interfaith couples do not have any right to appeal.

- Article 24 lists several rules that a non-Buddhist husband needs to abide by in his marriage with a Buddhist wife from Myanmar. For example, he is required to allow his wife to freely profess and practice her Buddhist faith, but he does not automatically receive the right to freely profess and practice his own faith. The rules also include broad and vague prohibitions against “insults” against Buddhism and Buddhists in general.

- If a Buddhist woman from Myanmar divorces her non-Buddhist husband, he must give away his part of their shared belongings and pay her compensation. The wife is also granted custody of any children they have together and the divorced husband must pay for their maintenance. These rules favour Buddhist women from Myanmar over their non-Buddhist husbands.

In 2014, the Monogamy Bill was also adopted. This law makes polygamy illegal. Extramarital affairs are also prohibited by this law.

One human right relevant for minority groups in this law is:

-

The law recognises polygamous marriages which spouses entered into before 2014 and does not criminalise these.

There are some restrictions and violations of minority rights in this law:

- Any marriage entered into after 2014 is deemed illegal if there is more than one spouse. Polygamy had been allowed in Myanmar until 2014 and was sometimes practised by minority and majority religious groups.

- Any person found guilty of illegal polygamy loses their property rights. The second spouse will not have any inheritance rights, and the person who has married twice can also not inherit anything from their second spouse.

The Population Control Healthcare Law was adopted in 2015. This law aims to establish “zones for healthcare” where special programmes are to be implemented to control the overall population size and to improve the overall public health situation.

One human right relevant for minority groups in this law is:

-

The law intends to promote goals that could also benefit minority groups. These goals are described with broad and vague words, such as “improve living standards while alleviating poverty”, “ensure sufficient quality healthcare” and “develop maternal and child care” (article 3).

There are some restrictions and violations of minority rights in this law:

- This law is vague and does not clarify what socio-economic indicators are used to measure if a State or Region should be a “zone for healthcare”. It could therefore be used arbitrarily in areas where many members of minority groups live.

- This law enables broad restrictions and violations of sexual and reproductive rights, the right to privacy and other rights of target groups, including minority groups. Implementers at the Regional or State level are allowed to prescribe rules for “persons receiving healthcare”. “Healthcare” is defined as “safe population control healthcare” and includes awareness-raising about “birth spacing”, which is defined as “having at least a 36-month interval between one child birth and another for a married woman”.

The Religious Conversion Bill was adopted in 2015. This law regulates how people can convert from one religion to another. Persons who want to convert to another religion need to apply to a Registration Board at the township level. The Registration Board mainly consists of government officials, except for four “local elders”. If an applicant fulfils the criteria for conversion, the Registration Board will issue a certificate of conversion.

Some of the human rights relevant for minority groups in this law include:

- The preamble includes a broad reference to citizens’ freedoms to choose, profess, practise and convert to religions. Furthermore, the law gives a right to persons to convert multiple times, should they wish to do so (article 4(b)).

- The law could give protection against religious abuse and promote the freedom of religion and belief. For example, the law states that it is prohibited to force a person to change their religion “through bonded debt, inducement, undue influence or intimidation” (article 15). The law also states that it is prohibited to “hinder, prevent or interfere” with someone who wishes to change their religion (article 16).

- The law makes it possible for some applicants, including persons with disabilities, to be issued a certificate of religious conversion through a quicker process or without having to appear in person to the Registration Board (article 9).

There are some restrictions and violations of minority rights in this law:

- Persons wishing to convert from one religion to another are required to undergo an application process and an interview with government officials. Therefore, their self-identified faith is put under scrutiny and registered. This violates individuals’ freedom of religion and belief and their freedom of thought and conscience. It may also interfere with religious and customary conversion practices used by religious minority groups.

- Applicants are required to study the religion they wish to convert to for at least 90 days. They need to study “the essence” of that religion, its laws related to marriage, divorce and property, and its customs related to “inheritance and custody of children” (article 7(d)). The law does not explain how these aspects of religion are to be identified and learned. It only states that the Registration Board can arrange for applicants to meet with “those with expertise and knowledge” of the religion.

- Article 14 prohibits people from converting to another religion “with the intent of insulting, degrading, destroying or misusing any religion”. This broad and vague language could enable arbitrary accusations against converts.

- Article 25 states that “religious conversion is not concerned with citizenship under this law”. However, the application form for religious conversions includes a question about the applicant’s scrutiny card number. This could restrict the right to religious conversion for stateless persons.

Ethnic Rights Protection Law, 2015

This law is sometimes referred to as the Indigenous Persons’ Rights Protection Law. The law establishes a Union-level Ministry of Ethnic Affairs to support the realisation of the rights stated in article 4. This Ministry is led by a Minister of Ethnic Affairs, who is appointed by the President. The Ministry has to coordinate and cooperate with other Union-level Ministries and Regional and State governments. The law additionally establishes Ministries of Ethnic Affairs, with their respective Ministers of Ethnic Affairs, at the Regional and State level and in Self-Administered Zones and Divisions. These ministries receive funding from the government of their respective area. The law also outlines ways to raise complaints if any articles in the law have been violated.

Some of the human rights relevant for minority groups in this law include:

-

Article 4 identifies different economic, social, cultural and political rights granted to these “ethnic groups”, including organising ceremonies, using traditional medicines and accessing education, healthcare and employment.

There are some restrictions and violations of minority rights in this law:

- In this law “ethnic groups” refers to people who are considered indigenous to Myanmar and therefore are entitled to CSCs. The law does not apply to associate and naturalised citizens.

- The budget to the Ministries of Ethnic Affairs comes from governments at the State, Region or Self-Administered Zone or Division level, and ministries in poorer areas of Myanmar might have a very limited budget.

- The law repeats the use of the disrespectful term “less-developed ethnic groups,” which also appears in the 2008 Constitution.

- Article 3 mentions objectives that some ethnic groups might disagree with.

- The law does not require that ethnic groups give their free, prior and informed consent before and during projects that are carried out in their areas. The law also only gives them a limited right to access information about such projects.

- Ethnic groups only have the right to teach their language and culture if this is not against any education policy at the central government level.

- Ethnic groups only have the right to teach about their histories and to preserve their heritages if this is “in accordance with the law”.

- The law includes broad and vague reasons for restricting rights of ethnic groups.

Rights of Persons with Disabilities Law, 2015

This law describes persons with disabilities as “persons who have one or more” long-term impairments, “either from birth or not”. The law recognises “physical, vision, speaking, hearing, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments”. The law describes disability as their inability “to fully participate in society due to the various barriers and hindrances in the physical and environment, attitude and perspective and others”.

A person can register as a person with disability in order to access rights in the law. However, this law does not list what criteria a person needs to meet in order to be registered. Associations, organisations and schools can also apply for registration under this law in order to provide services to and promote the rights of persons with disabilities.

The law is influenced by principles of non-discrimination (articles 9 and 12 and chapter 16) and accessibility (article 28). It aims to promote wide recognition of the dignity and abilities of persons with disabilities, to promote their equal inclusion in all fields of society, and to reduce and eliminate discrimination against them. Violations of any of the rights in the law are regarded as police cases and perpetrators can be punished.

The law lacks some details. Additional details are expected to be included in future by-laws.

Some of the human rights relevant for minority groups in this law include:

- Civil rights, such as the right to citizenship (article 8) and the right to freedom of religion (articles 14 and 16).

- Political rights, such as the right to vote in elections (article 29) and the right to become a Member of a Parliament (article 30).

- Economic rights, such as the right to be employed and the right to access tax relief or tax exemption for businesses run by persons with disabilities (article 35).

- Social rights, such as the right to inclusive and special education, basic and higher education and formal, non-formal and vocational education (articles 22 and 25), the right to access free or affordable healthcare (article 27), the right to access habilitation, rehabilitation and housing services (article 32).

- Solidarity rights, such as the law establishes special days and weeks to commemorate persons with disabilities (article 85).

There are some restrictions and violations of minority rights in this law:

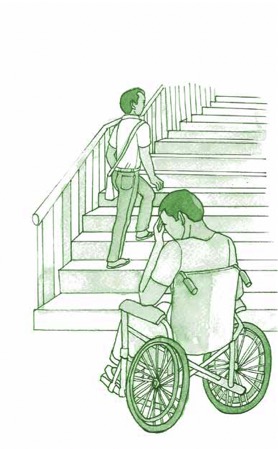

- The law does not fully promote inclusion, independent living and Universal Design principles. For example, it gives a right to people and organisations to establish special education private schools, but not private schools wherein students with disabilities are mainstreamed.

- Article 27(f) allows for adult women with intellectual impairments to reproduce, but only if they have consent from their parents or guardians. This can reduce the independence of these women.

- Article 30 gives a right to “citizens” with disabilities to be elected as Members of Parliament, but only in accordance with the 2008 Constitution and national elections-related laws. These laws prohibit persons with mental, intellectual and cognitive impairments from becoming Members of Parliament.

REFLECTION/DISCUSSION

- Do the Race and Religion Protection Laws affect men and women differently? If so, how?

- Do the Race and Religion Protection Laws affect people of different faiths differently? If so, how?

Educator’s notes

The Race and Religion Laws have been heavily criticised by many actors, including for providing “a legal framework to exacerbate ethnic, religious and communal tensions, incite violence, and perpetuate institutionalized discrimination against Muslims in Myanmar” (Equality Myanmar 2016:8).

The Myanmar Buddhist Women’s Special Marriage Bill might lead to the disregard for certain women’s self-identification with religions of their own choice. This is because “a woman may be branded a Buddhist, purely on account of her parents, unless she explicitly and manifestly identifies herself as following a different religion” (Equality Myanmar February 2016:10).

Since the law states that a Buddhist woman under the age of 20 years need her parents’ consent to marry a non-Buddhist man, it is discriminatory on both grounds of biological sex and religion (Equality Myanmar February 2016:11).

This law also violates the internationally recognised prohibition on retroactive application of laws. This is because article 28 states that “if a non-Buddhist woman converts to Buddhism after her marriage to a non-Buddhist man, the Interfaith Marriage Law becomes retrospectively applicable” (Equality Myanmar February 2016:10). This would trigger the application of Buddhist family law, even if other religious laws were applicable to the couple when they entered into marriage. This could potentially have a negative effect on the non-Buddhist spouse, as Buddhist family law might give more rights to Buddhist female spouses of non-Buddhist male spouses, in cases related to child custody, divorce, and inheritance (Crouch 2015).

When the non-Buddhist spouse is the one who decides to divorce his Buddhist female spouse, she could be favoured by the Myanmar Buddhist Women’s Special Marriage Bill. This is because article 27 states that if he “causes emotional stress or pain to his wife”, she will be granted many more rights compared to him after a divorce. Equality Myanmar (2016:11-12) has noted that the terms “emotional stress or pain” are “subjective, hard to quantify and verify, and very open to vague interpretation and manipulation”.

Moreover, the Myanmar Buddhist Women’s Special Marriage Bill grants a much stronger right to freedom of religion and belief to Buddhist women from Myanmar than the rights granted to members of other religions, regardless of their biological sex, gender identity, ethnicity or nationality. Thus, this law is discriminatory and favouring of Buddhist women from Myanmar (Equality Myanmar February 2016:11).

The Monogamy Bill “is fundamentally discriminatory towards a range of groups, though particularly non-Buddhists, women, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer people” according to Equality Myanmar (February 2016:14). The law does not recognise transgender persons, nor same-sex marriages (Equality Myanmar February 2016:14-15).

Equality Myanmar has also warned that the Population Control Healthcare Law might “be used arbitrarily against certain religious or ethnic minorities to harass, charge, arrest, sentence or jail them for a breach” (February 2016:9). It is particularly concerning that the law grants power to authorities to designate a geographic area a “zone for healthcare” and where “organizing” of “birth spacing” may happen. The law does not give any “transparent guidance” as to what criteria a geographic location needs to meet in order to be declared a “healthcare zone”. This leaves authorities with far-reaching powers to intervene in the private life of married couples, including a possible right to impose birth spacing of 36 months between live child births (Equality Myanmar February 2016:9-10). Amnesty International has warned that the law might enable “coerced contraception [use], forced sterilization or abortion” (Amnesty International 2015). Local policies limiting ethnic Rohingya women to only having two children have previously been in place in some locations in Rakhine State (Lewa 2012).

The Religious Conversion Bill discriminates against members of various religious groups because it formalises how conversions need to occur and be registered. Any religious conversion that takes place outside of the rules stated in the law and which has not been properly documented in a certificate “is not valid under Myanmar law” (Equality Myanmar February 2016:14). This means that religious and customary practices and ceremonies of conversion are not recognised as legal.

Conversions also need to be overseen by a Registration Board. Human Rights Watch (HRW) has warned that “the make-up of many local boards will be [consisting of] predominantly ethnic Burman Buddhist officials, who may be biased against conversions from Buddhism to other religions” (HRW 2015).

အမျိုးသားရေးဝါဒီ

လှုပ်ရှားသွားလာနိုင်မှု

အမွေအနှစ်

ကိုလိုနီဝါဒ